The Evolution of Money

Written by Paul Siluch

September 5th, 2025

Once upon a time, one of your neolithic ancestors – let’s call her Lilly - was hungry. She had a spare deer hide but nothing she could eat.

Her neighbour – let’s call him Ug - caught some fish and offered her two in exchange for the fur. She demanded four but the two settled on three because he was cold, and she needed to eat.

This was barter, the earliest form of monetary transaction.

Sources for data used: Historycooperative.org – The History of Money.

What makes any form of money work? There are five qualities:

- Durability - it must last.

- Portability – you must be able to carry or move it.

- Uniformity – it must be similar for every transaction

- Limited supply – it should be hard to copy.

- Divisibility – it should be able to be used for small transactions.

AI Image

In the story of Lilly and Ug, the fish succeeds in two, maybe three qualities of money. Same for the fur hide.

Barter is very subjective to the situation. Lilly needed food and Ug needed warmth, so a deal was struck. Barter systems were perfect for paleolithic trade and were the most prevalent form of commerce until around 3,000 BC.

Selling with Shells

Around 2,000 BC, seafarers like the early Phoenicians began using cowrie shells as a form of money.

Another one of your ancestors, Mago, had an amphora of wine he wanted to sell. Jezebel owned an embroidered tapestry. Each wanted what the other had and, thanks to an agreed value of each cowrie shell, the exchange became much easier.

It helped that cowrie shells were recognizable, durable, and rare in many inland cities.

Freepik

This was the era of commodity money. Salt was also a form of commodity money, as were cattle.

Settling with Metal

Not everyone wanted or trusted shells, however. They may be rare inland but everywhere near the ocean.

And if you wanted something worth half a cowrie shell, did you break one to pay for it?

And so began the metal money era.

Metal is rarer – and more easily divisible – than shells. Or cows, for that matter. Ingots of bronze, silver, copper, and gold could be weighed into precise units that everyone recognized. These were the first forms of metal money.

Dreamstime

Around 600 BC, the Turks, Greeks and Persians all began issuing standardized coins.

The Greek goddess of memory was called Mnemosyne. The Latin name “moneta” evolved from her name with the meaning “to remind.” Coins could have imprinted images stamped into them so people knew what country they came from, the king who issued them, and what they were worth. This conveyed information - a form of memory.

When the Romans adopted coinage on a much larger scale, these embossed coins came to be called moneta, or money.

Coin-based money had its own drawbacks. It was heavy to haul around, especially the cheaper denominations of copper and bronze. Large purchases involved tonnes of coins, which were risky to transport. Trade worked, but it was slow and cumbersome.

Along came the Chinese with another monetary invention.

Paper Money

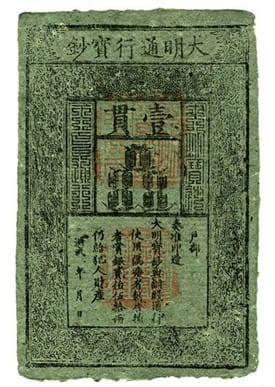

Around 600 AD, the Tang and Song dynasties began issuing paper-based currencies, a radical invention which relied on trust.

Trust in the lender, trust in government, and trust in the paper itself.

By the mid-900s and after many bankruptcies, the Song Dynasty backed its paper currencies with bronze and iron. This may have been the first paper money with hard assets backing it.

Marco Polo described China’s paper currencies to an incredulous Europe when he returned from the Orient in 1295, although it took another 400 years before Sweden issued Europe’s first true banknotes. They were backed by gold and silver coins, making them even more trusted (Spink.com).

Money.org

Tally Sticks

Paper money had its advantages, but also a host of disadvantages. Bank notes can be created with nothing to back them up, and paper is easy to counterfeit. Just like today.

University of Cambridge

The English came up with an interesting solution.

- Take a stick of hazel or willow.

- Mark notches to indicate the amount of money owed.

- Split the stick lengthwise so the grain is clearly visible. When the two halves are matched, the identical grain makes it impossible to counterfeit.

The tally stick was a contract between a debtor and a creditor embedded in the perfect match of the wood grain. Tallies were sanctioned by the king, could be traded like money, and were almost impossible to fake.

Wooden sticks eventually became too fragile and cumbersome so were abolished in 1826. They were burned in the furnaces of the House of Parliament in 1834 and ignited such an inferno, the medieval Palace of Parliament in London burned to the ground.

We worry about our money going up in flames. Theirs actually did.

(source: The Gower Initiative for Modern Money Studies)

Cryptocurrencies

Cryptocurrencies blend the best features of metal money and tally sticks with the blazing speed of the internet.

Bitcoin is the cryptocurrency we hear of most. The unit is only half the magic, however.

Every cryptocurrency, like bitcoin, is the train. The track it rides on is the blockchain. What makes the pair so powerful?

- Every bitcoin unit is mathematically unique and cannot be counterfeited.

- Every transaction is stored and “remembered” by the blockchain ledger – the railway – it rides upon.

Between the two, cryptocurrencies remember every person who has ever owned a bitcoin and every transaction it has been part of.

Bitcoin has a big problem, however. It moves up and down in price daily, like gold. Wal-Mart would have to reprice everything by the second to keep up with bitcoin’s price fluctuations, making it almost impossible to use as a currency. You don’t use gold to buy your groceries for this very reason.

Enter the stablecoin. Stablecoins do everything bitcoin does, except they never change in price. Like a dollar bill, it is worth the same yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

A stablecoin is like an 8-cylinder, fuel-injected, turbocharged dollar bill compared to the horsedrawn carriage of paper dollars we use today. Transactions happen in milliseconds anywhere in the world.

The U.S. government recently passed the GENIUS Act, which stands for Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins. This licenses, regulates, and provides all the guidelines for new stablecoins that link to the U.S. dollar.

This means the race is on for every company to accept or issue stablecoins. Will they replace traditional cash and credit cards? Not right away, but expect to see an explosion of usage in the years ahead with this new form of money.

Who wins?

Consumers.

Think of foreign exchange transactions done for pennies. Savings accounts don’t have to pay zero at the bank because you can zip your money somewhere that pays better. No transfer fees.

Retailers.

Big retailers like Amazon and Wal-Mart pay 1-3% in credit card fees today. They pass these costs on to you.

Who is at risk?

Banks.

Banks make their money off millions of chequing and savings accounts that pay close to 0%, then lend it out at 5%. If they lose this cheap savings pool, they are at risk. Loans and mortgages could be found at much lower rates through stablecoins.

Credit cards.

Stablecoins will be less expensive and faster. There will be enormous pressure on credit cards once stablecoins arrive, and debit cards too.

Now, banks and credit card companies have an amazing ability to adapt and absorb competition. Debit cards transact at lower rates than credit cards. They were adopted and absorbed by the banking system years ago. The internet was supposed to put credit cards out of business. Instead, they moved their telephone-based networks online and found ways to charge even more through loyalty point reward systems.

Can the financial giants adapt again by adopting stablecoins? History says they can and will.

You.

Transactions in stablecoins can be seen by everyone, especially governments. Say goodbye to paying cash to hide from taxes – anonymity becomes a thing of the past. Governments could also put time limits on stablecoins. Imagine a payment from the government that vanishes in 30 days unless you spend it.

Cryptocurrencies have no central authority. This means anyone who wants to hide their money can, including criminals. By regulating and shepherding new stablecoins, governments will have far more authority than they have with bitcoin.

In the end, it will come down to trust. And incentives. Will investors trust a US government-controlled digital currency, and will it hold its value? There are big advantages with lower transaction costs and speed but say goodbye to your anonymity and privacy forever.

And can governments be trusted to not rev up the digital printing press when they need money?

Like the advent of self-driving cars, expect to see many technology changes in the next few years.

A government-backed stablecoin will be one of them.

Corrections and Bargains

A recent Maclean’s article says condominium prices in Toronto have declined 16% since the peak in 2022. Other reports say the decline could be as bad as 21%. This is terrible news for those who bought high, but welcome news for those trying to get into the market.

In the stock market, Canada’s S&P/TSX index trades for approximately 19x earnings (Factset) versus its average of about 15x over the last twenty years. This is higher than normal. Several sectors, such as technology and mining, are at multi-year highs and have pushed index valuations to today’s levels.

Areas of more interest to bargain shoppers like us are banks, which trade at about 15x earnings - about their 20-year average p/e level. Energy shares trade well below their 20-year average (both measured by iShares sector ETFs).

Similarly, the US market is expensive on the surface, thanks to the Mag 7 technology stocks. Some sectors, however, have rarely been less expensive.

The drug sector – pharmaceuticals, as measured by iShares ETFs on the NYSE – trades near the lowest price/book and price/cash flow levels of the last 20 years. The U.S. government wants lower drug prices and is not happy with the industry. Neither are investors, it seems.

Same thing for the Food and Beverage industry. Kraft Heinz is splitting in two because of weak sales, and PepsiCo has activist investors demanding a realignment of its many brands. The industry, as measured by the Nasdaq Food and Beverage group, trades at the lowest price/book value in 20 years.

Markets, as a whole, are on the expensive side. A correction in the autumn months would help to alleviate this.

Meanwhile, there are bargains in unpopular places. That’s where we are looking.