Where Were You in '52?

Written by Paul Siluch

March 10th, 2023

A money manager remarked this week that many, many things in the economy depend on when the Ukraine war ends.

It was just a year ago that Russia invaded Ukraine. Putin, hoping for a quick victory, was surprised by Ukraine’s tenacity. He was even more shocked by the unity of the West in its assistance to the smaller nation.

Now, a year later, both sides find themselves dug into a trench war reminiscent of WWI.

To my mind, the era this is most similar to is the period from 1950 to 1953. These were the years when Dunkin’ Donuts, Walmart, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Denny's were all publicly listed, but they are not the parallel I am referring to.

1950 to 1953 were the years of the Korean War. This was the first of the modern so-called “proxy wars” where superpowers battled in distant lands inside other nations using foreign soldiers – “proxies” – as their agents. In 1950, it was the communist bloc of the Soviet Union and China battling the United States in Korea. We know now that it escalated, with the west (including Canada and Australia) sending in troops directly.

On a military level, the Korean War ground to a stalemate in 1953 at the 38th parallel, a no-man’s land that came to be known as the DMZ – the demilitarized zone. It stands today as one of the most peaceful areas of continuous tension in the world. It ushered in the global Cold War that flared for another 40 years.

On an economic level, the Korean War marked the end of the easy-money years following WWII. Interest rates had been forced down from 1939 to 1948 to allow western nations to repay their enormous war debts. The bubble burst when inflation bubbled up and the new conflict arose.

Does this sound a bit like today’s pandemic response, when we fought a global war against Covid-19? And borrowed so heavily to finance lockdowns? It should, for there is a direct parallel.

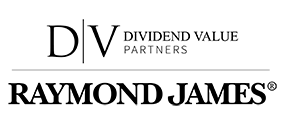

By 1950, inflation was on fire, a result of all that cheap money issued during the war years. It peaked at 10 per cent.

Excess savings from the war years pushed post-war demand higher, just as shortages (Europe had no soap, for example) pushed supplies lower.

Again, sound familiar? Cheap money and stimulus payments in 2020, followed by supply chain logjams in 2021, then raging inflation in 2022.

The cost of war to the U.S. from 1950 to 1953 was far higher than what the U.S. is spending on Ukraine today, but then again, we are only a year in to this war. Costs could grow. The Federal Reserve was as worried in 1953 about inflation as it is today due to prices of such things as rice because of the crop failures in Korea. To counteract rising prices, the Fed doubled interest rates from 1949 to 1953. Income and other taxes were also hiked to balance the budget. Imagine that governments once actually cared about zero debt!

Today, we finance everything. The entire Ukraine expenditure – every javelin missile, every tank – has been paid for through deficit spending. So far, anyway. It is a bill to eventually be paid through higher taxes or devaluation.

Today’s inflation was boosted from the rise in oil, coal, fertilizer, and uranium prices following the 2022 invasion. These commodities have since fallen back, but they acted as a springboard to other costs in society, like wages and rent. The inflationary waver we hoped was “transitory” has lasted longer than anyone expected. Inflation is a very hard rot to cut out once it takes hold.

"If something cannot go on forever, it will stop."

- Herbert Stein, economist

Eventually, the Ukraine war will end, either through victory or exhaustion, and a new DMZ will be drawn. What happened after 1953 is instructive to investors today:

- Inflation and shortages happen before and during wars. It happened in 1951, and happens every time.

- The end of war leads to slowdowns or recessions. It happened in 1954, and happens every time.

- The U.S. Federal Reserve operates under a “don’t just stand there, do something!” mindset. Inflation had fallen from 10-2 per cent by 1952, and yet the government was hiking rates through 1953. This led to the sharp, but brief, recession of 1953-4.

- T-Bill rates were slashed in half by 1954 (source: govinfo.com). Long-term interest rates also fell, and bonds rallied. Stocks dropped 10 per cent from 1952 to 1953.

- Interest rates stayed flat for a few years, then gradually climbed as recovery took hold. Stocks rallied after their 1953 bottom.

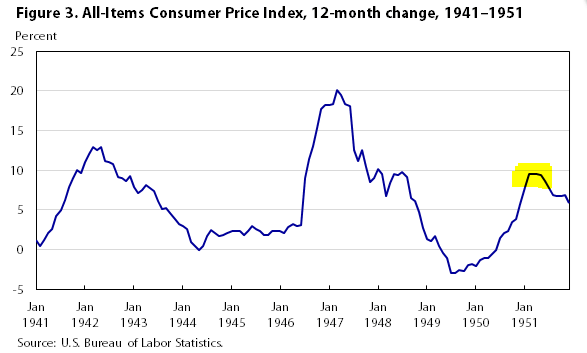

- After peaking at 10 per cent in 1951, inflation stayed below four per cent until 1968, when the next war – Vietnam – heated up.

The U.S. Federal Reserve held rates far too low after WWII and then hiked them too far by 1953. They made the natural cycle – inflation after war shortages, followed by deflation when war ends – worse. Just as they have today.

“History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.”

-Mark Twain

2023 is not destined to repeat 1953, but there are parallels:

- Wars (and pandemics) cause inflation. This one did. The end of wars is deflationary. Will this one be any different?

- We can see a recession on the horizon – how can you not when interest rates have risen so quickly? The Fed risks making it worse with too many rate increases.

- We can already see the end of the rate hikes – Canada is officially on “pause”, while other nations are still raising rates. Canada was the first to tighten aggressively, and now we are the first to stop. Other nations will follow.

- Longer-term bonds should rally from here, especially as a recession becomes more apparent. Stocks probably don’t go lower than last year, but they have a few dips ahead.

- The 1950s were a decade of geopolitical tensions that never resulted in global war, but still necessitated higher defence The world cut its war budget in 1946 then regretted it when the Korean War broke out. Today, we find ourselves just as unprepared and undersupplied as we did back then. Defence spending is likely to follow the same higher trajectory as the U.S. and China face off with one another.

- The 1950s were also a time of rapid exploration for oil and minerals. We face shortages of copper and rare earth metals today, so don’t be surprised to see more mines spring up after an entire decade where we stopped looking.

- The 1950s also saw rapid expansion of new technologies, such as IBM mainframe computers and jet airplanes. Today, the parallels are artificial intelligence, robotics, and the electrification of transit.

Inflation will solve itself, and the sooner the Ukraine war ends, the sooner this happens. Central banks have likely tightened too far and, as happened in 1954, will be cutting rates before they expect.

Markets this week

February was not kind to stocks, and March has not changed much.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average is negative for the year and is back to November levels. Canada’s index is still +3 per cent for the year, but we have given up some ground, as well. All bear markets end, but they feel like they last forever.

Bear markets don’t scare you out. They wear you out.

Where there is pain, there is also opportunity. The entire banking sector fell hard this week on fears that higher lending rates will result in a rash of bankruptcies. Canadian banks, and the larger U.S. banks, are broadly diversified and can weather rising loan losses. If bank stocks fall to the October lows, it will be a welcome opportunity.

As mentioned previously, High Interest Savings Accounts offer very competitive rates today:

- Manulife High Interest 4.40%

- BMO High Interest 4.35%

One-year GICs have dropped slightly from 5 per cent to 4.75 per cent, and two-year from 4.6 per cent to 4.35 per cent. These are still significantly higher than last year, so take advantage before they drop further.